Books

-

February 6, 2006 - Volume 84, Number 06

- pp. 29-31

Three Takes On Haber

Broader availability of Fritz Haber's personal papers has led to intriguing portrayals of his life

MASTER MIND: The Rise & Fall of Fritz Haber, the Nobel Laureate Who Launched the Age of Chemical Warfare, by Daniel Charles, HarperCollins, 2005, 313 pages, $24.95 (ISBN: 0-06-056272-2)

EINSTEIN'S GIFT, a play by Vern Thiessen, directed by Ron Russell, U.S. debut at the Acorn Theater, New York City, October 2005

HABER, a film written and directed by Daniel Ragussis; debut set for spring 2006, 35 minutes

Fritz Haber (1868-1934) is one of science's greatest stars. He's also one of science's scoundrels. Haber is best known for devising a direct synthesis of ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen. Carl Bosch (1874-1940) later perfected large-scale ammonia production by Haber's method, an achievement that led to inexpensive fertilizers and increased food production worldwide. Haber received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918 for his ammonia work, and Bosch later shared the 1931 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his high-pressure methods.

Haber also is known for developing a synthesis of nitric acid from ammonia that was useful for producing explosives, as well as for synthesizing a variety of insecticides. He also proposed a plan to extract gold from seawater to help finance Germany's reparations and reconstruction after World War I, but it turned out not to be feasible.

Despite his positive contributions, Haber has been vilified for advocating the first use of chemical warfare in the early days of World War I. One of his insecticides, Zyklon B, later became a standard means for killing detainees in Nazi Germany concentration camps.

Little has been written about Haber's life until recently, because his papers had been kept locked away by a protégé. When the papers were made publicly available in the early 1990s, they opened the floodgates to myriad depictions of the scientist's life, first in German and now in English. C&EN takes a look at three of these works, a biography, a play, and a short film, that give details about a pivotal time for chemistry and for history.

Germany's Angel And Devil

Depending on whom you talk to, Fritz Haber was either a loyal, generous, and brilliant scientist or a power-hungry, egotistical, and morally bereft monster.

Either way, Haber's scientific legacy is unquestionable. His process for converting nitrogen into ammonia provides the fertilizer absolutely essential for large-scale agricultural production; notoriously, he also pioneered the use of chlorine and other gases as weapons in World War I.

Given that the entire world's food supply depends on Haber's technology, and the horror with which people view chemical warfare, it's surprising how infrequently Haber has popped up in popular scientific lore. Unlike those of his good friends Albert Einstein and Max Planck, Haber's life and legacy have remained shadowy.

Given that the entire world's food supply depends on Haber's technology, and the horror with which people view chemical warfare, it's surprising how infrequently Haber has popped up in popular scientific lore. Unlike those of his good friends Albert Einstein and Max Planck, Haber's life and legacy have remained shadowy.

Now, Daniel Charles' expertly written and meticulously researched book, "Master Mind: The Rise & Fall of Fritz Haber, the Nobel Laureate Who Launched the Age of Chemical Warfare," lays out Haber's complex life and the tragedies that eventually befell him as Hitler rose to power in Germany.

Haber's life and career were inextricably linked with the political upheaval in Europe that led to two world wars. He studied at several universities, receiving a Ph.D. in chemistry in 1891. After a few aimless years working for his father and trying to break into academia, he landed a position as a lab assistant at the University of Karlsruhe in 1894 and then rose through the ranks to become a professor. A passionate patriot characterized as having an undying love for Germany, Haber renounced Judaism and converted to Christianity, presumably to enhance his potential for an academic career.

As a young professor at Karlsruhe, Haber entered the race to make ammonia production from nitrogen and hydrogen industrially feasible. His discovery of a process using high pressure and temperature, initially with osmium as a catalyst, led to an almost immediate agricultural revolution. Fellow countryman Carl Bosch's work with an iron catalyst improved the process and allowed large-scale production.

Charles, a former technology correspondent for National Public Radio, draws an unsettlingly clear picture of modern agriculture, which took a great leap forward with the hyperproduction possible with cheap nitrogen fertilizers. Whether for good or bad, without the Haber-Bosch process, agriculture could not have expanded to support all the people in the world today.

At the beginning of World War I, Haber, by then director of Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry, in Berlin, solved another pressing industrial problem. He perfected a process for converting ammonia to nitric acid, which became a critical ingredient for making the nitrates used in explosives manufacture after British warships cut Germany off from ready supplies of nitrates from Chile. Also during World War I, Haber's group developed the use of hydrogen cyanide as an insecticide for flour mills and granaries. Known as Zyklon A, the gas contained an odorous marker as a warning system to prevent poisoning.

It was Haber who came up with the idea to use chlorine gas to subdue (via suffocation) troops in the trenches; he saw this type of weapon as no worse than bullets and artillery shells. He led a cadre of "gas soldiers," who painstakingly mapped gas delivery strategies. Chlorine was soon supplanted by phosgene (COCl2) and then by a far worse agent, mustard gas (bis[2-chloroethyl]sulfide).

Although Haber enthusiastically tackled the development of these hideous weapons, Charles is painstakingly careful to depict Haber as a contradictory character, "both a villain and a hero." Preserved in his letters is evidence that he elicited deep affection from many people. Yet much of his life remained troubled. He was a chronic insomniac dependent on sleeping pills, and he was forced to take regular breaks at a sanitarium for nervous conditions.

His first wife, Clara, was the first woman to receive a Ph.D. from the University of Breslau. Yet from all appearances, his forceful, domineering personality subsumed Clara's own quest for an academic career and left her depressed and bitter; she eventually commited suicide. His second marriage, to a witty businesswoman 20 years his junior, foundered and ended after 10 years.

Charles also points out that, though Haber won the Nobel Prize for discovering the ammonia process, he did not possess the intellectual acumen of his scientific compatriots, such as Einstein. Rather, it was hard work and luck that led Haber to his discoveries.

Despite Haber's outspoken loyalty to his country, his Jewish ancestry and wartime role made him undesirable in the eyes of Nazi Germany. In 1933, several months after he was forced to fire some of his staff, Haber left Germany. He was in his 60s then and in poor health. He traveled around Europe, trying to find an institution that would take him in. His quest ended when he died of heart problems in Switzerland in 1934. Ironically and tragically, Zyklon A, the HCN insecticide Haber originally introduced, had evolved to Zyklon B, the notorious poison used in Nazi Germany concentration camps. Among its victims reportedly were some of Haber's relatives.

The author does let a few items fall through the cracks. Though he explains in detail the chemistry and engineering involved in the Haber-Bosch ammonia process, he doesn't tell us about Haber's later industrial development for converting ammonia to nitric acid for weapons. Readers might also have appreciated a chemical description of mustard gas, which Charles neglected.

Charles runs out of steam toward the end of the book, and his pleasant, musical prose gives way to dry exposition. This story of Haber's life, however, is still a riveting reminder that human beings rarely fall exclusively on the side of good or evil.—ELIZABETH WILSON

The Mind And Soul Of Science

With our assessment of the 20th century—history's bloodiest—well under way, we find science circling its wagons, under attack by proponents of "intelligent design." Meanwhile, the world remains at code-orange alert with the threat of more terrorist attacks and the prospect that al Qaeda might go nuclear. What better time to stage a dialogue between Albert Einstein and Fritz Haber?

The timing is indeed perfect for Canadian Vern Thiessen's award-winning play "Einstein's Gift," which made its U.S. debut in New York City last October and ran through Nov. 6 at the Acorn Theater. The play, winner of the Governor General's Award for Drama (Canada's equivalent of the Pulitzer Prize), takes a critical look at where "new science for a new century" took us a century ago and where it might take us this time around.

The 20th century likely will stand as a culminating point for the Age of Reason, a time when mankind's willingness to pour its energy into mechanical, chemical, and nuclear warfare revealed what some have called the "lie of progress." With the increasing likelihood that science will find itself on the defensive in the 21st century, the contrast between two of history's greatest, most inventive scientific minds affords us a useful, if bleak, frame of reference.

Thiessen's play takes up the theme of humanistic versus amoral science, investigating distinct trajectories into the scientist's quest to improve the lives of others and to make a name for oneself. Einstein and Haber quite neatly represent opposite sides of this dichotomy as they spar throughout the play.

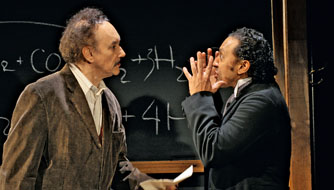

Photo by Dixie Sheridan Photo by Dixie Sheridan |

| EXISTENTIAL HEROS In Thiessen's play, Einstein (Shawn Elliott, left) and Haber (Aasif Mandvi) fight about the purpose of science at the dawn of a century of mass destruction. |

Haber, with his Prussian rectitude, baptism-of-convenience conversion from Judaism to Christianity, arch patriotism, and eager use of chemistry to promote the most abstract ideas in the worst possible way, was played convincingly at the Acorn by Aasif Mandvi. And Shawn Elliott's violin-toting, tweed-coat-with-a-stale-sandwich-in-the-pocket-wearing Einstein, the beleaguered humanist and optimist, was no caricature. Elliott opened a unique personal window on the modern age's best known scientist.

Although "Einstein's Gift" focuses on the rise and fall of Haber, it is very much Einstein's play. Einstein's character is staged as a cross between the narrator in Thornton Wilder's "Our Town" and Ebenezer Scrooge in Charles Dickens' "A Christmas Carol." We meet him as he sneaks onstage and begins puttering before the lights go down, politely waiting for the audience to notice him. He regards the house with a knowing, avuncular smile.

Throughout the play, he comments from the sidelines or steps into a scene from the past and relives it. He doesn't explain much. He reminisces: There was a time, he reminds us at several points in the play, when women spoke music, men thought poetry, and humanity moved into the future with the organic grace of the hands on a Swiss watch. Einstein, the conscience of the play, is of that time.

Thiessen views the two scientists as converging at a point of moral ambivalence. It is ultimately Haber's humanity that makes him a fascinating tragic figure, and Einstein, the Renaissance man, lives to see his science co-opted by the government-science establishment, brought to bear in the annihilation of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. As Einstein and Haber meet together at the end of evening, they are sidelined, watching as whatever it is that is wrong with mankind lunges forward under the aegis of science, whether the scientist likes it or not.

"Einstein's Gift" is hardly an antiscience screed, but chemists must be warned: Einstein's views on chemistry-the physicist calls it unimaginative, boring-may be tough to sit through. And some may share Haber's exasperation with Einstein's declaration that imagination is more important than knowledge. The play is ultimately an indictment of the unholy alliance of "industry, government, and science," which, as it turns out, are the words that Haber and others chant, in full uniform, prefiguring German fascism in militaristic fashion at the beginning of World War I.

Toward the end of the play, Einstein offers a "gift" of a tallith, or Jewish prayer shawl, that reaffirms the dying Haber's humanity and individualism and negates his earlier religious conversion. But it is only after the Nazis use Haber and discard him, making clear their views on humanity and individualism, that he is able to embrace what he had forsaken as a striving young man.

Thiessen, who is neither a scientist nor a historian, studied science and history to write a play about the mind and soul. All that study paid off, for "Einstein's Gift" shows that the human spirit, under siege, still has its moorings, that there is hope, even in the throes of nuclear conflagration. As for new science for a new century, Thiessen forecasts more of the same.—RICK MULLIN

Contradictions For Science And Society

When Germany went to war with Europe in 1914, one of its first strategic plans was to have Fritz Haber, "Germany's greatest chemist," help win the war through technology. "Haber," a new short film written and directed by Daniel Ragussis, is a well-thought re-creation that captures a snapshot of a few months of the Nobel Laureate's life during this critical period. The docudrama places the viewer firmly into the mind of the scientist as he struggles with difficult decisions that affected not only his life and legacy, but also the lives of his loved ones and millions of innocent others.

The film opens with Haber lost in thought, staring out of a train window while traveling through the German countryside. This scene cuts away to old black- and-white newsreel footage of Germany at war in World War I. The news changes to announce that Haber has won the Kaiser Wilhelm Medal for saving mankind from a famine of biblical proportions by developing a nitrogen-fixing process that allowed large-scale production of fertilizers. Ragussis aptly places the magnitude of Haber's discovery, that Haber is the top chemist in a country that at the time led the world in chemistry.

But the film "Haber" is not about his past successes. It is about his being pressed into service by the German government to help win the war. As a military officer tells Haber: "The only hope we have of survival is technology. That is why we asked your institute to evaluate the feasibility of a new idea: blowing gasses into the trenches, to clear them out."

Haber voices his reservations. "You saved millions with your last invention," the officer says. "This could save even more." Haber eventually concedes the reality of war, that people, especially young people, will continue to die. He accepts his fate and devises a plan.

His idea was to use chlorine gas to temporarily incapacitate enemy soldiers and take them out of the war, not to maim or kill them. The film portrays lab testing on a monkey and the decision to make the first use of chlorine in the trenches near Ypres, Belgium, in April 1915. Ragussis does a nice job describing in layman's terms that chlorine is an oxidizing agent and has a burning effect on organic matter, leading to severe irritation of the eyes, nose, and throat followed by a form of acute bronchitis. Cell damage leads to fluid buildup in the lungs, preventing oxygen from reaching the blood.

Photo by Johannes Kroemer Photo by Johannes Kroemer |

| TRAGIC DILEMMA Ragussis' film about Haber (played by Christian Merkel) depicts the scientist torn between science, morality, and national allegiance. |

According to the screenplay, Haber is a man full of ability and ambition yet torn by the costs of his success. He has strained relationships with his father and the rest of his family because he converted from Judaism to Christianity, an "adjustment" made to help his career. Haber faces his demons during the course of the film, and at one point he awkwardly ventures into a synagogue, presumably to make sure he has chosen the right path for his life. Is his faith in the right place?

The film depicts Haber witnessing his wife Clara's slow spiral to self-destruction. She was the first woman to receive a doctorate degree in chemistry at the University of Breslau. She also was ambitious, but taking time to start a family and supporting her husband's consuming career "intruded on her plans," a familiar scenario for women scientists. To ameliorate her depression, Haber tries to get her a university teaching position. But when he succeeds, she freezes in front of her first class and gives up.

Haber goes to Ypres to oversee the first use of chemical warfare. Cylinders full of chlorine gas are in the trenches, with bundles of hoses leading over the berm toward the enemy. As Haber prepares to go, Clara confronts him. She has discovered what is about to happen and urges him not to go. But he must. The film then alternates between Haber and Clara, each considering the position that they have come to in their lives.

The film takes us as far as the German soldiers starting to attack after the gas has dissipated. We don't know from the film the effectiveness of the chlorine, but descriptors at the end tell us it was a great, but temporary, success. Allied troops were able to recover from that first attack, and the war continued for another three years.

Haber returns home to learn that Clara has committed suicide in the garden, shooting herself through the heart. She appears to have finally been pushed over the edge by Haber's decision to continue in the gas warfare program. The film then ends as it begins, with Haber being given an award, this time the Iron Cross for service to Germany.

Alex Twersky and Chris Spanos produced "Haber" under the aegis of the nonprofit Haber Film Foundation (haberfilm.org), with major funding from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. The English-language film stars some of Germany's finest actors, including Christian Merkel as Haber and Juliane Köhler as Clara. It is being scheduled for the film-festival circuit, with a premiere expected this spring, and it seems destined to appear on television.—STEVE RITTER

- Chemical & Engineering News

- ISSN 0009-2347

- Copyright © 2010 American Chemical Society